Cover Image Generated by Gemini Nano

Cover Image Generated by Gemini Nano

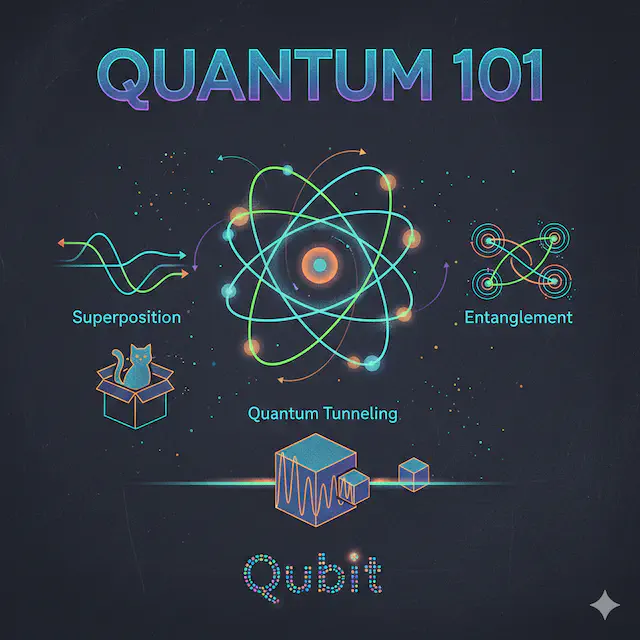

When I started learning quantum computing, I got overwhelmed by physics textbooks talking about wave functions, Hilbert spaces, and Schrödinger equations. Here’s what I wish someone told me on day one: you don’t need to understand all the physics to start programming quantum computers.

This post focuses on the core concepts you actually need to write quantum code: qubits, gates, and measurement. But before we write any code, let’s understand the fundamental building blocks.

Understanding the Basics: Before Any Code

What is a Qubit?

A classical bit is simple: it’s either 0 or 1. At any moment, you know exactly what state it’s in.

A qubit (quantum bit) is different. It can exist in a superposition of both 0 and 1 simultaneously. Think of it like a coin spinning in the air; it’s neither heads nor tails until it lands.

Mathematically, we represent a qubit’s state using ket notation:

$$|\psi\rangle = \alpha|0\rangle + \beta|1\rangle$$Let me break down this notation:

- $|\psi\rangle$: This is called a “ket” and represents the quantum state. The $\psi$ (psi) is just a name we give to this particular state.

- $|0\rangle$: The ket representing the “0” state (like a classical bit being 0)

- $|1\rangle$: The ket representing the “1” state (like a classical bit being 1)

- $\alpha$ and $\beta$: These are complex numbers called probability amplitudes

The key insight: $|\alpha|^2$ gives you the probability of measuring 0, and $|\beta|^2$ gives you the probability of measuring 1. These probabilities must sum to 1:

$$|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$$For example, if $\alpha = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$ and $\beta = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$, then:

- Probability of measuring 0: $|\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|^2 = \frac{1}{2} = 50\%$

- Probability of measuring 1: $|\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|^2 = \frac{1}{2} = 50\%$

What Does Measurement Mean?

Here’s the part that confused me for weeks: you cannot directly observe superposition.

When you measure a qubit, the superposition collapses to either $|0\rangle$ or $|1\rangle$ based on the probabilities. After measurement:

- The superposition is destroyed

- The qubit is now definitely in either state 0 or state 1

- You cannot “undo” the measurement

This is fundamentally different from classical computing where you can read a bit’s value without changing it.

Why this matters for programming: You can’t use print() or debuggers to “peek” at qubit values during computation. You have to design your algorithm so that the answer you want has high probability when you finally measure at the end.

What is a Quantum Register?

A quantum register is just a collection of qubits, similar to how a classical register is a collection of bits.

If you have 3 qubits, you have a quantum register that can be in a superposition of $2^3 = 8$ different states simultaneously:

$$|\psi\rangle = \alpha_0|000\rangle + \alpha_1|001\rangle + \alpha_2|010\rangle + \alpha_3|011\rangle + \alpha_4|100\rangle + \alpha_5|101\rangle + \alpha_6|110\rangle + \alpha_7|111\rangle$$This exponential scaling ($n$ qubits can represent $2^n$ states) is where quantum computing’s power comes from.

What is a Classical Register?

A classical register is just regular bits (0s and 1s) where you store the results after measuring qubits.

Think of it this way:

- Quantum register: Where the computation happens (qubits in superposition)

- Classical register: Where you store the final results (regular bits)

You need classical registers because once you measure a qubit, it becomes a classical bit. You store this result in a classical register so you can read it later.

What is a Quantum Circuit?

A quantum circuit is like a recipe or a program. It specifies:

- How many qubits you need (quantum register)

- How many classical bits you need (classical register)

- What operations (gates) to apply to the qubits

- When and which qubits to measure

- Where to store the measurement results

Think of it as a flowchart that reads left to right:

Qubits start → Apply gates → Apply more gates → Measure → Classical bits

Unlike classical circuits with AND/OR gates, quantum circuits use quantum gates that manipulate superpositions.

Now Let’s See This in Code

Now that we understand what these terms mean, let’s see how they work in Qiskit.

Setup

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister

from qiskit_aer import AerSimulator

from qiskit.visualization import plot_histogram

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# We'll use Aer's simulator to run our quantum circuits

simulator = AerSimulator()

Creating Your First Quantum Circuit

There are several ways to create a quantum circuit in Qiskit. Let me show you all of them so you understand what’s happening:

Method 1: Simple shorthand (most common)

# Create a quantum circuit with 1 qubit and 1 classical bit

qc = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

print(qc.draw())

This creates:

- 1 qubit in the quantum register (starts in state $|0\rangle$)

- 1 classical bit in the classical register (starts at 0)

q:

c: 1/

The qubit is labeled q, and the classical bit is in register c.

Method 2: Qubits only (no classical bits)

# Create a circuit with 2 qubits, no classical bits

qc = QuantumCircuit(2)

print(qc.draw())

q_0:

q_1:

This is useful when you’re just designing the quantum part and will add measurement later. You can add classical registers later with:

from qiskit import ClassicalRegister

c = ClassicalRegister(2, 'c')

qc.add_register(c)

q_0:

q_1:

c: 2/

Method 3: Using explicit registers (more control)

# Create registers explicitly

qreg = QuantumRegister(2, 'q') # 2 qubits, named 'q'

creg = ClassicalRegister(2, 'c') # 2 classical bits, named 'c'

# Create circuit from registers

qc = QuantumCircuit(qreg, creg)

print(qc.draw())

q_0:

q_1:

c: 2/

This approach is useful when you want:

- Multiple separate quantum registers

- Custom names for your registers

- More complex circuit structures

For example:

# Separate registers for different purposes

data_qubits = QuantumRegister(3, 'data')

ancilla_qubits = QuantumRegister(2, 'anc')

measurement_bits = ClassicalRegister(3, 'meas')

qc = QuantumCircuit(data_qubits, ancilla_qubits, measurement_bits)

print(qc.draw())

data_0:

data_1:

data_2:

anc_0:

anc_1:

meas: 3/

Method 4: Just quantum registers

qreg = QuantumRegister(3, 'q')

qc = QuantumCircuit(qreg)

print(qc.draw())

q_0:

q_1:

q_2:

Which method you should use?

For learning and simple programs, Method 1 (QuantumCircuit(num_qubits, num_cbits)) is the easiest and most readable.

Use Method 3 (explict registers) when:

- You’re building complex algorithms with multiple register types

- You want meaningful names for different qubit groups

- You’re working on a larger quantum program

For the rest of this tutorial, I’ll use Method 1 to keep things simple.

Understanding the Default State

Important: Qubits always start in the $|0\rangle$ state. This is the quantum equivalent of initializing a variable to 0.

Let’s measure this qubit immediately to confirm:

qc = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

# Measure qubit 0 and store result in classical bit 0

qc.measure(0, 0)

print(qc.draw())

┌─┐

q: ┤M├

└╥┘

c: 1/═╩═

0

The M is the measurement gate. The line connecting to the classical register shows where the result is stored.

Now let’s run this circuit:

# Run the circuit 1000 times

job = simulator.run(qc, shots=1000)

result = job.result()

counts = result.get_counts()

print(counts)

# Output: {'0': 1000}

What just happened?

- We created a circuit with 1 qubit (starting in $|0\rangle$)

- We measured it immediately

- We ran this 1000 times (“shots”)

- Every single time, we got 0

This makes sense—there’s no superposition here. The qubit is definitely in state $|0\rangle$, so measuring it always gives 0.

Quantum Gates: Creating Superposition

Now let’s introduce quantum gates; operations that manipulate qubits.

The Hadamard Gate (H)

The Hadamard gate creates an equal superposition. It transforms:

$$|0\rangle \rightarrow \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|1\rangle$$This means: 50% chance of measuring 0, 50% chance of measuring 1.

qc = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

# Apply Hadamard gate to qubit 0

qc.h(0)

# Measure

qc.measure(0, 0)

print(qc.draw())

┌───┐┌─┐

q: ┤ H ├┤M├

└───┘└╥┘

c: 1/══════╩═

0

Now run it:

job = simulator.run(qc, shots=1000)

counts = job.result().get_counts()

print(counts)

# Output: {'0': 506, '1': 494} (approximately 50/50)

This is the key insight: After applying the H gate, the qubit is in superposition. We can’t see the superposition directly, but when we measure 1000 times, we see the probability distribution; roughly half 0s and half 1s.

The X Gate (Quantum NOT)

The X gate is like a classical NOT gate: it flips the qubit:

$$|0\rangle \rightarrow |1\rangle$$$$|1\rangle \rightarrow |0\rangle$$qc = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

# Flip the qubit

qc.x(0)

# Measure

qc.measure(0, 0)

print(qc.draw())

┌───┐┌─┐

q: ┤ X ├┤M├

└───┘└╥┘

c: 1/══════╩═

0

Run it:

job = simulator.run(qc, shots=1000)

counts = job.result().get_counts()

print(counts)

# Output: {'1': 1000}

The qubit started as $|0\rangle$, we flipped it to $|1\rangle$, and every measurement gave us 1.

The Z Gate (Phase Flip)

The Z gate is trickier. It adds a negative sign (phase) to the $|1\rangle$ component:

$$|0\rangle \rightarrow |0\rangle$$$$|1\rangle \rightarrow -|1\rangle$$If you apply Z to $|0\rangle$ and measure, you’ll still get 0. If you apply it to $|1\rangle$ and measure, you’ll still get 1. So what does it do?

The phase affects interference. Let me show you:

# Circuit 1: H then H (they cancel out)

qc1 = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

qc1.h(0) # Create superposition: (|0⟩ + |1⟩)/√2

qc1.h(0) # Apply H again: back to |0⟩

qc1.measure(0, 0)

# Circuit 2: H, then Z, then H

qc2 = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

qc2.h(0) # Create superposition: (|0⟩ + |1⟩)/√2

qc2.z(0) # Add phase: (|0⟩ - |1⟩)/√2

qc2.h(0) # Apply H: transforms to |1⟩

qc2.measure(0, 0)

# Run both

counts1 = simulator.run(qc1, shots=1000).result().get_counts()

counts2 = simulator.run(qc2, shots=1000).result().get_counts()

print("Without Z:", counts1) # {'0': 1000}

print("With Z:", counts2) # {'1': 1000}

The Z gate changed the phase, which changed how the second H gate interfered with the superposition. This is quantum computing’s “secret sauce”; using interference to amplify correct answers and cancel out wrong ones.

Working with Multiple Qubits

Let’s create a circuit with 2 qubits:

qc = QuantumCircuit(2, 2) # 2 qubits, 2 classical bits

# Apply H to both qubits

qc.h(0)

qc.h(1)

# Measure both

qc.measure([0, 1], [0, 1])

print(qc.draw())

┌───┐┌─┐

q_0: ┤ H ├┤M├───

├───┤└╥┘┌─┐

q_1: ┤ H ├─╫─┤M├

└───┘ ║ └╥┘

c: 2/══════╩══╩═

0 1

Run it:

job = simulator.run(qc, shots=1000)

counts = job.result().get_counts()

print(counts)

# Output: {'01': 256, '00': 272, '10': 227, '11': 245} (~250 each)

With 2 qubits each in equal superposition, we get all 4 possible outcomes with equal probability!

The Basic Pattern of Quantum Programming

Here’s the structure you’ll see in almost every quantum program:

# 1. Create a circuit with qubits and classical bits

qc = QuantumCircuit(num_qubits, num_classical_bits)

# 2. Initialize/prepare qubits (they start in |0⟩)

# Often you create superposition here

qc.h(0)

qc.h(1)

# 3. Apply problem-specific gates

# This is where your algorithm goes

qc.x(1)

qc.z(0)

# 4. Measure qubits and store in classical bits

qc.measure(quantum_register, classical_register)

# 5. Run the circuit multiple times

job = simulator.run(qc, shots=1000)

result = job.result()

counts = result.get_counts()

# 6. Analyze the results

print(counts)

Key Takeaways

Qubits start in $|0\rangle$: Always. You need gates to create superposition.

Ket notation ($|0\rangle$, $|1\rangle$): Just a way to label quantum states. $|0\rangle$ means “the quantum state 0”.

Quantum circuits flow left to right: Initialize → Apply gates → Measure.

Measurement destroys superposition: Once you measure, you get a classical bit (0 or 1) and lose the quantum information.

You need many shots: Because measurement is probabilistic, you run the circuit many times to see the probability distribution.

Classical registers store results: Measurement converts quantum information to classical information.

What Confused Me (and Might Confuse You)

“Why can’t I just look at the qubit without measuring?” Because measurement fundamentally changes the quantum state. There’s no “read-only” access to superposition.

“If I can’t see superposition, how is this useful?” You design algorithms so that wrong answers cancel out (destructive interference) and correct answers amplify (constructive interference). When you measure, you see the right answer with high probability.

“What’s with all the square roots?” Probabilities must sum to 1. If you want equal probabilities for 2 outcomes, each amplitude must be $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$ because $|\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|^2 + |\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|^2 = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2} = 1$.

Try This Yourself

Before the next post, experiment with this:

- Create a circuit with 1 qubit

- Try different combinations of H, X, and Z gates

- Measure and run with 1000 shots

- Try to predict the results before running

Challenge: Can you create a circuit where measuring 0 has 75% probability and measuring 1 has 25% probability?

Next Steps

In the next post, we’ll explore entanglement: how to create quantum correlations between qubits where measuring one instantly tells you about the other. We’ll build the famous Bell state and understand why Einstein called it “spooky action at a distance.”

Until then, play with the code. Change the gates, observe the results, and build intuition. Quantum programming is learned by doing.